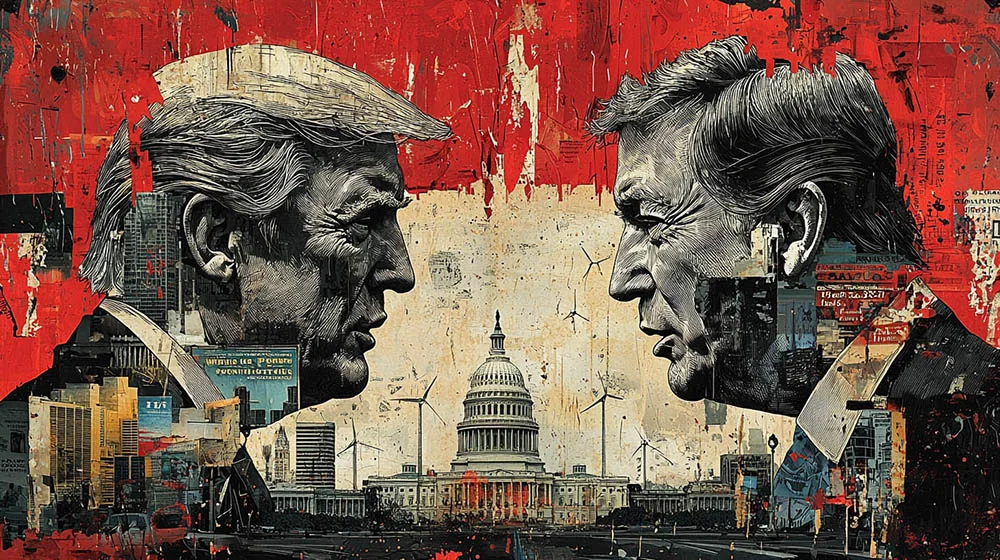

America First or America Isolated? Trump’s Foreign Policy Gamble

If America must be ruthless, it should at least be strategic. That is the hope President Donald Trump’s defenders cling to as he blames Ukraine for its own invasion and aligns himself with Russia at the United Nations. His supporters argue that his seemingly baffling concessions to Vladimir Putin are part of a grand geopolitical maneuver—a calculated effort to pull Russia away from China, America’s most formidable rival. This so-called “reverse Kissinger” strategy attempts to mirror the Cold War diplomacy of President Richard Nixon and his adviser, Henry Kissinger.

At first glance, the analogy appears to hold. In the early 1970s, Kissinger, serving as Nixon’s chief diplomat, orchestrated a groundbreaking rapprochement with Chairman Mao Zedong, China’s Communist leader. At the time, Mao was a ruthless dictator with blood on his hands, and his primary foreign policy goal was to end American support for Taiwan, which he viewed as a breakaway province. Declassified transcripts reveal that Kissinger, during his secret visits to Beijing, hinted that the United States might not block a Chinese takeover of Taiwan, going well beyond the official U.S. stance.

Nixon’s motives were complex. Some were pragmatic, such as the hope (ultimately futile) that China would assist in ending the Vietnam War. Others reflected his broader vision of America’s role in maintaining global stability. In 1967, Nixon wrote, “We simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates, and threaten its neighbors.”

However, Nixon and Kissinger’s initial goal was not to wield a “China card” against the Soviet Union. Rather, they sought to curb China’s support for Maoist insurgencies worldwide. They also hoped that improved Sino-American relations would unsettle the Soviet leadership, prompting them to pursue arms control agreements and other forms of détente with Washington. Only later did the U.S. and China form an anti-Soviet partnership, which included CIA-backed listening posts in Xinjiang to monitor Soviet missile tests. Over the following decades, China aligned itself with the West, not the Soviet Union, in its modernization efforts.

Misreading History, Misjudging the Present

Today, members of Trump’s inner circle offer various justifications for ending Ukraine’s war and rehabilitating Putin’s international standing. Most of these rationales revolve around China. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth justifies America’s declining commitment to European security by stating that “the United States is prioritizing deterring war with China in the Pacific.” Vice President J.D. Vance calls it “ridiculous” for America to “push Russia into the hands of the Chinese” and equally “ridiculous” for Russia to accept a junior partnership with Beijing. To Trump’s allies, this strategy is not only pragmatic but also in line with America First principles.

Unfortunately, it is both a flawed historical parallel and a misguided contemporary analysis. Most crucially, America did not drive China and the Soviet Union apart. By the late 1960s, the former allies were already on the brink of war. Maoist China, driven by revolutionary zeal and nationalist fervor, accused the Soviet Union of “socialist imperialism,” branding it worse than Western capitalism. At one point, 45 Soviet divisions were stationed along the Sino-Soviet border, and tensions escalated into artillery exchanges, raising fears of nuclear war.

Today, the power dynamic has reversed. China is the dominant force, with Russia increasingly reliant on Beijing. While Putin chafes at this dependence, the reality is inescapable. Following Western sanctions after its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has turned to China as its primary market for energy exports and a key supplier of industrial components, especially those crucial for military production, such as drones, missiles, and tanks. Though Putin has hinted at China’s tough negotiating tactics when buying Russian energy, trade between the two nations continues to flourish, reinforcing their economic interdependence.

While their diplomatic and security interests are not always perfectly aligned, the differences are not as stark as they were between China and the USSR in the Cold War. Chinese scholars privately argue that European criticism of China’s indirect support for Russia in Ukraine is unfair, yet they acknowledge that this perception has harmed China’s standing in Europe. Similarly, Chinese analysts express unease about Russia’s growing military ties with North Korea, fearing that Pyongyang might be rewarded for its support with advanced weapons that could destabilize the region. However, this is a far cry from 1969. Russia is not terrified of China, nor is China fearful of Russia. Instead, both countries see themselves engaged in a long-term struggle against American global influence—one that will persist regardless of who occupies the White House.

Selfishness Is Not Strategy

For those who wish to cast Trump as a master strategist, one fundamental problem remains: there is little evidence that he sees himself in the mold of Nixon and Kissinger. Trump appears impatient with geopolitics and uninterested in the idea that other nations have deep historical grievances and ideological commitments. He views ideology as little more than an obstacle to deal-making. By contrast, Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin are acutely aware of history and adept at using geopolitical tensions to consolidate power at home. Both leaders leverage external threats and fears of Western influence to justify domestic crackdowns and expand their authority.

If Trump is isolating any country, it is his own. By distancing the United States from its European allies and undermining the Western alliance, he is not executing a shrewd diplomatic maneuver—he is weakening America’s global position. His supporters may call this ruthlessness. Kissingerian cunning it is not.

Related New: