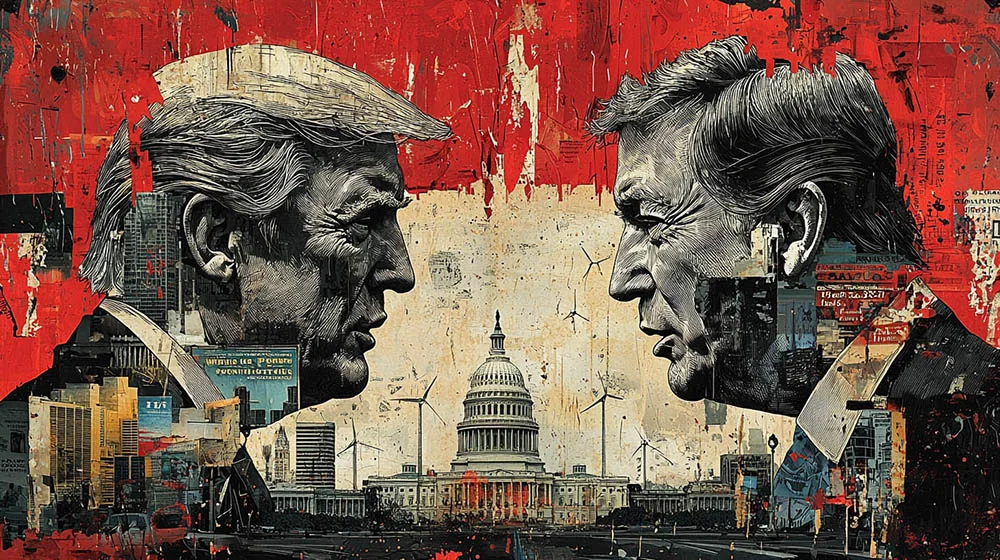

Who Should Represent Europe Against Trump and Putin?

Beyond his gravelly baritone and his penchant for treating geopolitics like a Tetris puzzle, Henry Kissinger is often credited with a quip he may never have actually made: that he never knew whom to call to speak to Europe. Decades later, in the age of Zoom diplomacy, that question remains just as unresolved. However, with potential peace talks over Ukraine looming, Europe can no longer afford ambiguity. The continent must put forward a single representative—someone who can hold their own in photo-ops with Vladimir Putin (representing Russia’s authoritarian interests), Donald Trump (representing, above all, Donald Trump), and perhaps even Volodymyr Zelensky (Ukraine’s embattled leader).

While it is easy to identify figures who would be unacceptable to one faction or another, finding a candidate who could credibly represent Europe as a whole is far trickier. With over 40 countries that rarely see eye to eye, Europe typically responds to major diplomatic moments by sending multiple envoys. But this time, that luxury may not be available. Trump, for better or worse (mostly worse), is driving the early stages of negotiations—convening preliminary talks in Saudi Arabia without the involvement of Ukraine or Europe. If he deigns to include Europe at all, he is unlikely to grant it more than a single seat at the table. Ukraine has urged Europe to present one name, but has stopped short of suggesting who it should be.

The EU’s Default Candidates: Costa and von der Leyen

The most straightforward option would be to nominate a leader from the European Union’s upper echelons. Among its many "presidents," the European Council’s leader is officially tasked with representing the EU at the head-of-state level. But António Costa, the new incumbent, would be a problematic choice. As a former Portuguese prime minister, he is more of a behind-the-scenes operator than a commanding international statesman. Furthermore, his selection would alienate Britain, a key supporter of Ukraine, whose interests would hardly be represented by an EU bureaucrat. Given Trump’s deep disdain for the EU—often derided by his allies as a supranational deep-state machine—any EU institutional figure, including Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, is likely to be dismissed out of hand.

Macron: The Frontrunner with Baggage

An obvious alternative is to turn to Europe’s national leaders. In the past, this role would have naturally fallen to Angela Merkel, Germany’s longtime chancellor and the continent’s chief powerbroker. However, Merkel is long gone, and her likely successor, Friedrich Merz, will need months to assemble a governing coalition following the February 23rd elections—leaving him little bandwidth for international diplomacy.

That leaves France, Europe’s second-largest power. Emmanuel Macron has a strong claim to the role of “Mr. Europe.” He handled Trump during the latter’s first term and demonstrated a solid rapport with him in their February 24th meeting at the White House. France, like Russia and the United States, is a nuclear power with a permanent UN Security Council seat. Moreover, Macron’s vision of European “strategic autonomy”—less reliance on America—has only gained relevance in recent months. Paradoxically, domestic turmoil at home frees him to focus on foreign affairs.

Yet Macron carries baggage. Northern and central European hawks deeply distrust him, particularly regarding Russia. Before 2022, he advocated for a “strategic dialogue” with Moscow, an approach that now looks naive. Though he has since shifted to a more hawkish stance—being one of the first to suggest that European troops might be deployed to Ukraine—skepticism lingers.

The Case for Tusk: The Hawk from Eastern Europe

For those wary of Macron, Poland’s Donald Tusk presents an alternative. His country understands the Russian threat better than most, spending the highest share of GDP on defense of any NATO country—a stance that aligns well with Trump’s demands for greater European defense spending. However, Poland has ruled out sending troops to Ukraine and maintains a complicated relationship with Kyiv. Tusk himself has another liability: he openly disparaged Trump while out of office, a move that may not be easily forgotten. He also shares foreign policy oversight with Poland’s president, who is set to be replaced in June by an unknown quantity. Western Europeans, meanwhile, are reluctant to entrust their most hawkish member state with a mandate to negotiate on their behalf.

Other Contenders: Long Shots and Compromises

Beyond Macron and Tusk, few realistic candidates emerge. Spain is geographically distant from Ukraine, and its prime minister, Pedro Sánchez, has not been among Kyiv’s most vocal backers. Britain’s Sir Keir Starmer sees the UK as a potential “bridge” to America, but Brexit has left the country diplomatically sidelined in Europe. Italy’s Giorgia Meloni is an ideological ally of Trump but has yet to resolve how to balance pro-Ukraine and pro-Trump positions.

A compromise could be found in a respected leader from a smaller European nation—someone like Petr Pavel, the Czech president and a retired general. However, Trump, who thrives on dominance politics, would likely dismiss any consensus pick with a condescending “Who is this guy anyway?”

The Unavoidable Conclusion: Macron Must Lead

Given the options, Macron remains the most viable choice. He wants the role and has already convened European leaders in Paris to prepare for it. He also made a concerted effort to consult widely before his recent three-hour discussion with Trump. To assuage those concerned about his geopolitical instincts, his mandate could be balanced with strong deputies—such as Kaja Kallas, Estonia’s foreign-policy hawk, who could serve as a counterweight in preparatory talks with the U.S. secretary of state.

Europe’s inability to present a single voice has historically been part of its charm and complexity. But in a world dominated by hard-power politics, that luxury is no longer viable. A single representative, even one who unsettles some, is far better than the alternative: being shut out of the conversation entirely.

Related New: